Uniting farmers in Middle America and fuckboys in Manchester, workwear is perhaps the only genre of fashion capable of straddling socioeconomic, geographic, and political fault lines. Over the past decade, the convergence of popular fashion and workwear, whereby throngs of city slickers dress like off-duty manual laborers, has seen entire neighborhoods enveloped in tobacco-colored chore jackets and jauntily-angled beanies. Consider Kaia Gerber, Jonah Hill, Bella Hadid, and Daniel Day-Lewis, who are all frequently photographed cosplaying as Brooklyn handymen.

The trajectory of workwear can be mapped onto the ascendancy of its flagship brands. Carhartt, for example, was founded in 1889 in Michigan for railroad workers, yet it’s now a staple of mainstream streetwear. What started out as a humble uniform supplier, has become a niche, subcultural(-ish) signifier, beloved by skaters and musicians, rappers and graffiti artists, graphic designers, and freelancers. The same goes for Stan Ray, a West Texas family-owned brand that has suddenly become the go-to for your favorite skater's favorite pair of pants. But whether you're wearing these pieces for the fashion clout, or for their original purpose (to work), the end result is the same. Workwear has slowly become part of everyone's rotation. Affordable and hard-wearing, these products have become an evergreen alternative to the hamster wheel of fashion’s trend cycle — a clarion call for authenticity.

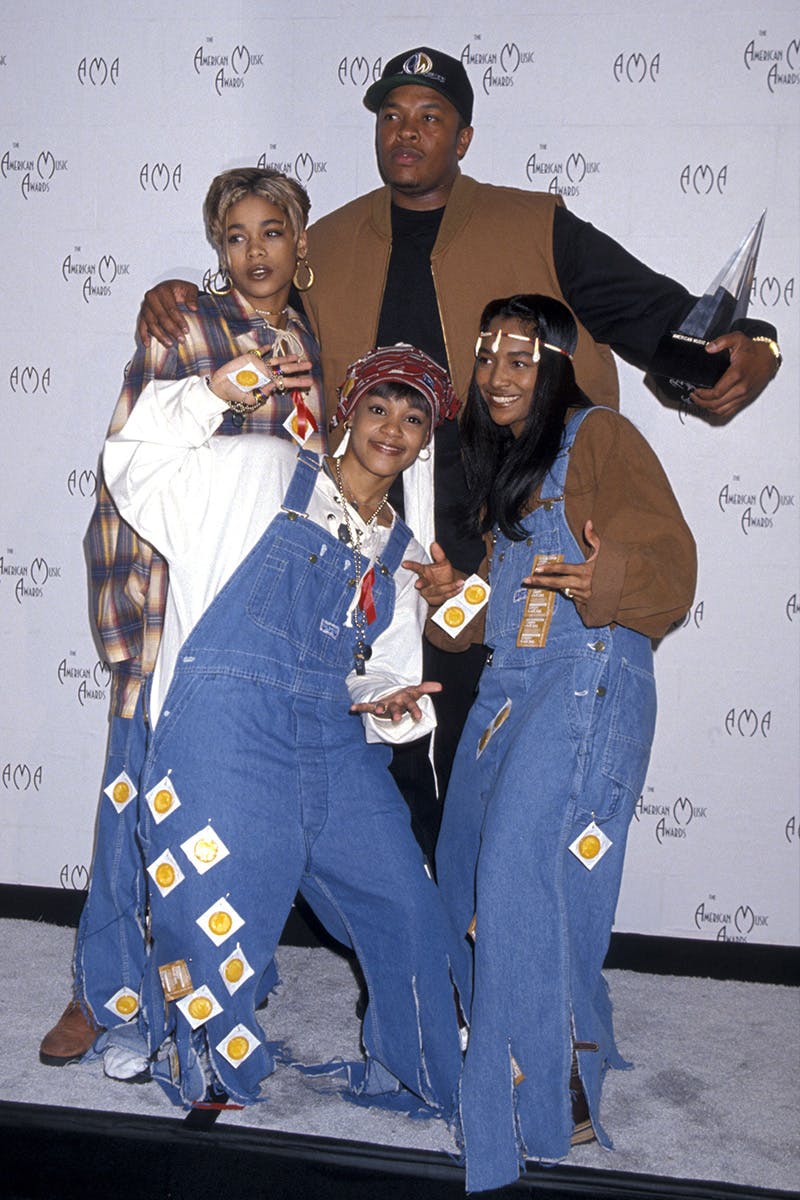

Our current obsession with workwear can be traced back to the likes of Tupac, Nas, Public Enemy, and Dr. Dre, among plenty of hip-hop’s frontmen throughout the 80s and 90s. Unassuming and gritty, labels like Carhartt, Timberland, and The North Face spoke to rap’s steely exterior, which it projected onto rugged fabrics, blown-up silhouettes, and utilitarian pockets.

All the imposing, baggy fits, chimed with hip-hop’s hypermasculine bravado, while its working-class provenance had natural gravitas on the streets of Compton, Harlem, and Chicago’s South Side. After all, it was the hardworking underdog who first wore steel-capped boots, square duck jackets, and cargo pants. And just as rural, blue-collar workers were grateful for their functional garb, so too were the city’s late-night hustlers, who valued durability, warmth, and above all, an inconspicuous uniform. Three decades later, workwear remains a symbol of humility within hip-hop, offsetting the genre’s more ostentatious wielding of brands like Balenciaga, Rick Owens, and Raf Simons.

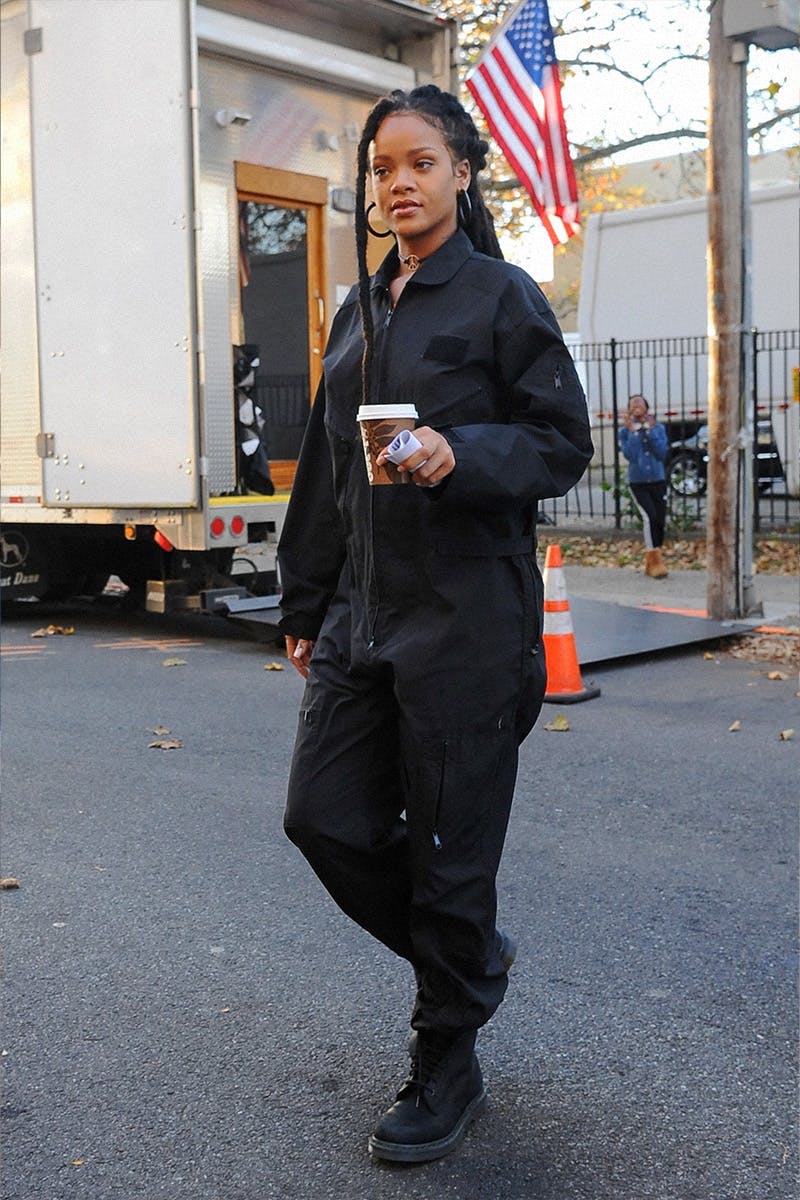

Nowadays, you can find the likes of Drake, ASAP Ferg, and Lil Yachty all regularly brandishing workwear looks without anyone batting an eyelid. Most recently, a notable moment was A$AP Rocky wearing a vintage denim Carhartt jacket in the photo that announced Rihanna's pregnancy to the world.

But it's not just in street style that workwear is still making an impact, it's become an accepted piece of Red Carpet attire. An obvious patron has been Kanye West, who famously wore a $43 Dickies jacket to the Met Gala and has continued to wear Carhartt's golden ‘C’ from all the way back during his Yeezus era. Pete Davidson also wore a similar Dickies jacket at an award show recently, something fans speculated wasn't a coincidence, and we mustn't forget when Timothee Chalamet rocked up on the red carpet in paint-splattered dungarees.

These celebrity parties and award shows are a long way from the construction sites which workwear was first created for. And it must be noted that, as much Carhartt has aligned itself with these zeitgeisty figures, it has always remained at a distance from fashion’s epicenter, carefully skirting the industry’s trappings by cozying up to its subcultures.

It was Edwin Faeh, an unknown German businessman, who shoulders most of that responsibility. In 1994, having noticed the proliferation of brown canvas within youth culture, Faeh managed to sign a licensing deal between his own brand, Work in Progress, and Carhartt, which gave way to Carhartt WIP, setting up a direct line to the cutting-edge crowds which were already rummaging through flea markets for its parent label. And though the two brands are related, they are different entities. WIP took Carhartt’s workwear codes and applied them to a lean, streetwear vision, bending (ever so slightly) to wider fashion trends. In the space of five years, the brand had launched its own skate team and record label, shooting skaters, who were known shoplifters, for its lookbook. Cue a series of savvy collaborations – including Vetements, Junya Watanabe, and Undercover – and Carhartt had found itself, quite literally, in the lap of luxury.

Only, workwear has always been a part of high fashion parlance. Yohji Yamamoto has been making moody, industrial-luxe clothing for decades, while Miuccia Prada continues to send out barracks worth of nylon, a fabric widely used in WWII, alongside a facsimile of uniforms pilfered from nurses, janitors, firefighters, and builders. The same goes for a younger generation of designers, too, like Craig Green, Kiko Kostadinov, Samuel Ross, Heron Preston, and the late Virgil Abloh, who all have built menswear dialects around workwear. And over the past three years, laborers have lugged their wares down almost every major runway, twisted to apocalyptic effect by Marine Serre, Demna Gvasalia, and Kim Jones. However, workwear’s relationship with luxury fashion has been an awkward one.

For many, it’s been an incongruent, and somewhat appropriative, clash of worlds. The price of these garments alone outstrips most blue-collar wages, not to mention that 25% of manufacturing positions have vanished since 1950. Fashion’s history is testament to this conflict, given that denim was first worn by miners and that Chanel’s trademark LBD was plucked from 19th-century maids. It dins into one of fashion’s inner struggles, that the industry is not, in fact, an exclusive business for exclusive people, but that it’s real, just like the workers it inhabits. It’s little wonder, then, that workwear saw such a resurgence in the 2010s, when dungaree-toting millennials began to sniff at consumer culture, romanticizing independent roasteries and thrift stores for their authentic origins.

For all of its overtures to authenticity, consider workwear the new heritage. Given that today’s construction workers are more likely to wear cheap sportswear than they are workwear labels, the popularity of the style gestures to something more nebulous, to the idea of something democratic with real history. Only, wearing an actual heritage label would be to align yourself with a musty elite, or worse, flag some kind of privilege. Whether or not workwear is classless, though, is academic. It has flourished where heritage has floundered.

Perhaps workwear’s parlay into streetwear was best summarised in 2010 by the French filmmaker Mathieu Kassovitz, who dressed the protagonist of his cult classic, La Haine, in a Carhartt beanie. “He’s honest and doesn’t need much money. He’s an urban survivalist. And that’s why he wears Carhartt.” In workwear, Kassovitz found a symbol of streetsmart, and while it’s easy to prod at the way in which the look has been gentrified, for those who wear double-front jeans, rough-cut jackets, and boxy overshirts, it’s all very anchoring. Be that on a skater, laborer, or Hollywood actor, workwear is a case of both style and substance.

Shop the best workwear for men below

Detroit Jacket

Carhartt WIP

Spaces T-Shirt

Carhartt WIP

Medley Tote Bag

Carhartt WIP

Trucker Jacket

One Of These Days

Deaver Flannel Shirt

Carhartt WIP

6 Inch Premium Boot

Timberland

Double Knee Pant

Carhartt WIP

Marfa Hoodie

Carhartt WIP

Leisure Pants

One Of These Days

Glenn Shirt Jacket

Carhartt WIP

Heritage Rubber Toe Hiker

Timberland

Syd Beanie

Carhartt WIP

New Tools Cap

Carhartt WIP

6 Inch Premium Boot

Timberland

New Tools Cap

Carhartt WIP

Double Knee Pant

Carhartt WIP

Heritage 6 Inch Premium

Timberland

Montana Pant

Carhartt WIP

Trade Single Knee Pant

Carhartt WIP